Denis Legezo is a cybersecurity specialist who moved from Russia to the United Kingdom on a Global Talent visa. Below is Denis’s own first-person account: an honest story about relocation, choosing a country and a school for his daughter, applying for a visa, and adjusting to a new life.

At Relogate, we especially value stories like this — when people who moved to another country with our help share what this journey actually looks like from the inside. Perhaps this story will become a point of reference for someone, or an opportunity to try this path on for themselves.

Today, it’s much easier to ask any LLM about relocation like this. You don’t really need people for that anymore. But there’s still a useful genre called data points — for those who are still figuring things out. And models have to learn from something, after all.

So here, let’s try to understand whether you even need to move to the Island at all — and if you do, what to be prepared for in terms of expenses, moving your belongings, and visas.

I’m a Muscovite with forty years of life experience. A year ago, I moved to London with my small family, after spending two years living in Yerevan. This is a story about fairly spontaneous decisions — and about how for some people the dream destination is Tbilisi, for others Los Angeles, and only you know which one is yours.

Professionally, for the past twelve years I’ve been working in corporate security — I’m an infosec specialist. I’ve been in IT for over twenty years overall. My roles are usually called security engineer or security researcher.

Those twelve years break down into nine years at Kaspersky and three years at Yandex. In the first case, I was protecting external clients; in the second, the company’s own employees, services, and hardware.

Overall, that’s a decent starting position for relocation. Few people in Europe know Yandex, but almost everyone knows Kaspersky. I’m often asked whether the latter was a disadvantage when applying for a visa. No — it was actually a plus. It’s very international work, and so far it has been the best job I’ve ever had.

From a family perspective, we have one child, now 11 years old, who moved to secondary school this academic year. At the start of our emigration, she was eight, and in the UK we still caught the final stage of primary school.

Everything began with Armenia, and the decision to leave Russia was primarily driven by our child’s education — and by the fact that the public sphere was increasingly overpowering the private one.

What’s happening in Russian schools today doesn’t work for us. I strongly believe in teaching how to think, not what to think. Does London offer that? I’m not entirely sure yet — but it seems more yes than no.

So, at the starting line we had: over forty years lived in Moscow; a solid list of completed projects, published articles, and books read; a relatively small number of obligations back home; solid American-style English; basic German and Spanish; a passport; a five-year Dutch Schengen visa that expired during COVID; and an active one-year Indian visa (India as a country for immigration is probably too much — but I did consider it).

There’s an important point here. If you’re Russian and not an idiot (idiots, in my experience, usually have no self-esteem issues at all), you are very likely underestimating yourself. Sometimes seriously. Try letting someone else look at you from the outside. Honestly — tell someone about yourself and about what you’ve actually done. The perspective can shift quite suddenly.

Any decent relocation consultants can quickly assess how well you fit a particular visa. If you’re a highly functional nerd who enjoys digging into rules and regulations, you can absolutely bury yourself in the paperwork on your own. In my case, consultants turned out to be useful — more on that later.

I mentioned obligations back home for a reason. I understand they matter. But it’s worth asking yourself honestly whether you’re using them as an excuse for “doing nothing.”

With this set of circumstances, I agreed with a friend — for which I’m very grateful — that I would stay with them in Yerevan at first, and I bought my first ticket. A week after arriving, I was frying eggs in my rented apartment in Tsaghkadzor. Two months later, 350 kilograms of belongings arrived in the Yerevan district of Arabkir — and shortly after that, my family followed. Renting, shipping, and moving all went fairly smoothly, but you’re here to read about the UK, so I won’t dwell on it.

I’ll just say that, based on my limited experience, the first months of any emigration hit me hard: I’m irritated, grumpy — and then it passes, and things get better.

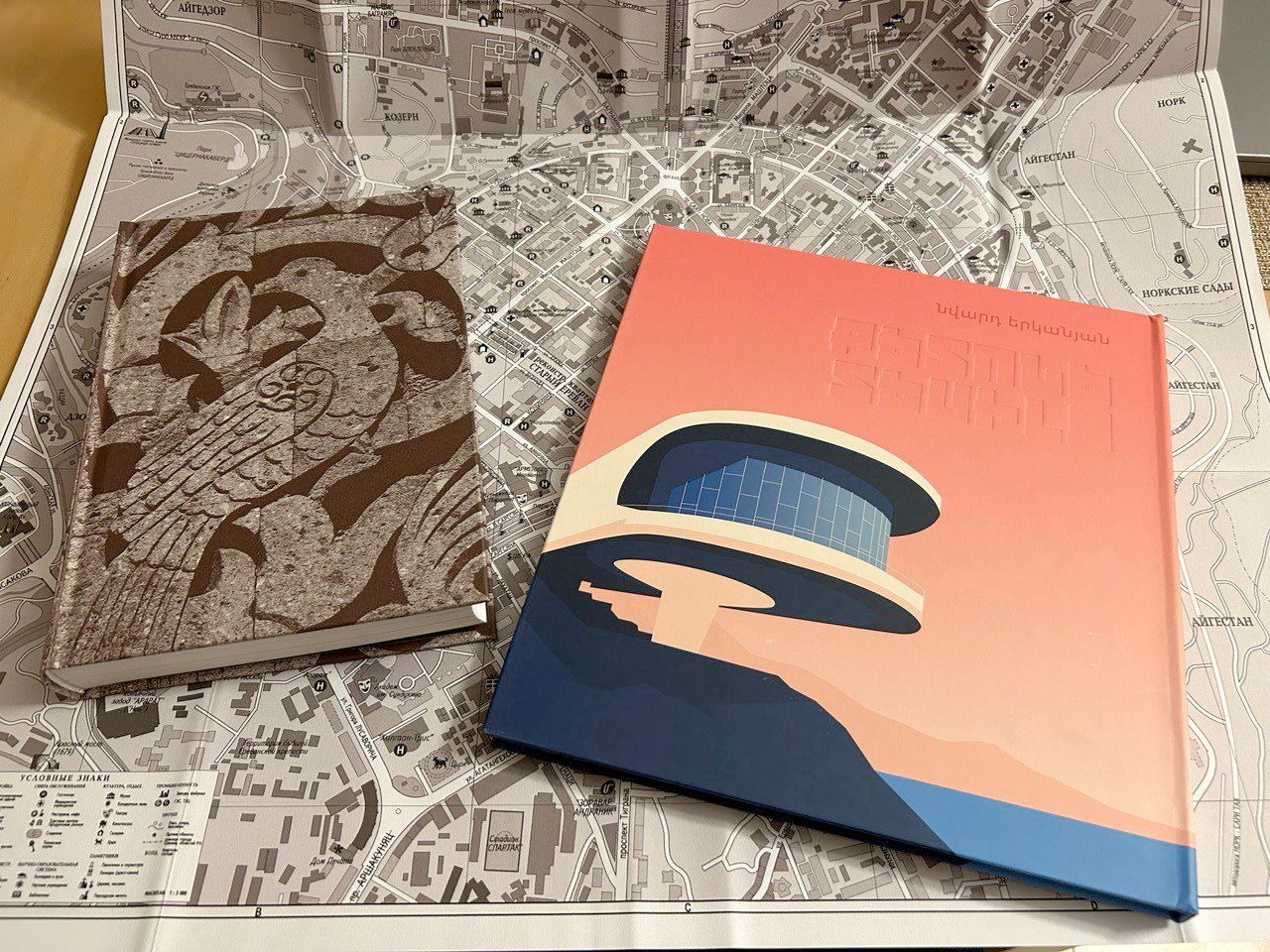

I can’t say nothing about Armenia — sorry about that. I’ve grown quite attached to it, to put it mildly. Before all this, I knew almost nothing about Yerevan (and even less about Tsaghkadzor). Having no expectations is the key to success: Armenia exceeded them easily on every front.

At first, it was standard эмигрант routine: telecoms, banks, legalisation, tax numbers, an apartment, and work in the country.

Out of those two years, I spent about a year and a half learning Armenian. I never actually started speaking it — the city functions very well in Russian — but I can read (not to be confused with understanding what I read) and type. That’s already something. Armenian script, by the way, is very beautiful, and the keyboard layout is phonetically identical to Latin, so you start touch-typing fairly quickly. Even reading shop signs and metro directions isn’t useless — it gives you a different sense of the city. If you have the resources, learning the local language is absolutely worth it.

Armenia, to my taste, is surprisingly good — and it’s the people who make it so. Calm, boastful, attentive to others, with an unpredictable length of the “Armenian half-hour” (which does eventually arrive, even if three days later), charismatic, sometimes exhaustingly talkative, and with enormous experience of living alongside Russians. Our sudden influx didn’t seem to bother anyone much. Armenians came back from Syria and Iran — now Russians have arrived; fine. They pay taxes, buy goods, and don’t cause trouble.

At first, my daughter attended a local neighbourhood school nearby — a ten-minute walk from home — but fairly quickly moved to the Armenian branch of the private Neube(r)g school, about thirty minutes away on foot. It was opened by teachers who had left Russia.

Regular neighbourhood schools are somewhat weaker than the average Moscow school. I think it’s fair to compare them to regional schools in Russia. The two most well-known private schools founded by Russians, on the other hand, are noticeably stronger than the average neighbourhood schools in Moscow.

There is also the IB (International Baccalaureate) option, if you’re aiming for universities in other countries later on. In Yerevan itself, joint universities have been opened by all major diaspora countries — Russia, France, and the United States. Diasporas matter here: out of roughly 10 million Armenians worldwide, about 7 million live outside the country.

There is also Ayb School, founded by Davit Yan, and another school in Dilijan opened by Ruben Vardanyan. I’ve only seen the latter and don’t know much about it, but at Ayb you can’t study without a serious command of Armenian — and that’s absolutely right. It’s the same logic Kaha Bendukidze once used in Georgia, when he opened a university teaching in the national language: “An elite educated in Cambridge won’t be able to become local politicians — they won’t have the necessary adult Georgian language.”

I suspect that if people have other options and no particular ties to Armenia, few would consciously choose to live in Yerevan. At the same time, I know people who have returned there from London — and I understand them.

What I also understand is the confusion of foreign universities and employers: “Where is that, exactly? What do they teach there, and how do people work?”

When someone hears the words “a London school,” a certain image immediately appears — not necessarily a positive one, but one shaped and promoted over centuries. With “a Yerevan school” or university, there is no such image abroad. Not because they are bad, but simply because the world doesn’t know what that is.

This is where we gradually move toward London — a place where, sooner or later, you have to answer a simple question: “Why am I here for this amount of money?”

That answer comes more easily to people building fintech startups, and is harder for many others.

Russians (and Chinese) tend to be deeply focused on their children’s education. My theory is that education has historically been our main social elevator. So for us, schools and universities can serve as an answer to that question. If you think in terms of where it will be easier for a child to move forward in life, British education may not be the worst step. Not because London or its schools are perfect — far from it. But because it is, in every sense, a language that opens doors and will continue to do so for the next generation.

It is a well-established intellectual conveyor belt — an education system that everyone understands. No one will customize it for you, but it is a route the world knows how to read. That is the difference with Armenia, and the motivation to move further.

Let’s talk about the visa. As you might guess, I used the help of immigration consultants. In my case, I clearly understand their added value: the ability to identify the right KPIs and to present achievements properly. It’s much easier to write in a confident, even pompous tone about someone else than about yourself.

At some point in Yerevan, a Relogate sales manager messaged me — I had come up in their recommendations as someone with a suitable profile. They suggested discussing immigration options. The list was standard: France, the UK, the US, and the UAE. The last two were a definite no. I’ve been to both several times, and without a strong need to live in the US or on the Peninsula, I wouldn’t choose them.

I fully understand that the Island is not for everyone either. So in the end, the choice came down to continental Europe versus the UK. Given my profile, the consultant recommended applying to the latter — which is what I did.

On the surface, the advantages were obvious: the language. The downside was that the UK is no longer in the EU. On the other hand, it has its own kind of CIS — in the form of former distant colonies.

Let me repeat an important point for those who are planning. Russians are often very bad at bragging.

“What problems did you solve on the project?” — “Oh, I just did it, nothing special.”

“Who’s a global talent?” — “Me? Surely not.”

So it helps to mentally rename this visa from “talent” to “the woodpecker visa” — the one for people who peck through all the paperwork. It has only a very indirect relationship to your actual talent. You may be talented, or you may not — that’s almost beside the point.

What feels like “just part of the job” to you can turn out to be a meaningful achievement when viewed from the outside.

And now, finally, it’s time for a bit of advertising. My case was prepared by Anya Uzhinova — a Relogate expert who had previously worked at Kaspersky herself and understood me almost instantly. My involvement was minimal: just a few interviews.

She translated my biography into the language of Tech Nation criteria — highlighting numerical KPIs where needed, emphasising scale where it mattered. What I described as “I built a couple of tools” became “developed an analysis framework that saved researchers a measurable number of man-hours.”

A separate, minor source of stress was writing to former managers asking for recommendation letters. It feels like you’re asking for an awkward favour. But, surprisingly, no one refused. Everyone responded kindly. And even the strictest of them said: “There are a lot of wild exaggerations, but no lies.”

That was the most honest and, at the same time, supportive feedback possible. I now see the application as bragging without lying. The problem is that we — the last generation of pioneers — usually lack the habit of bragging properly.

In the end, it took about four to five weeks to gather all the documents and submit them at the Yerevan TLS centre (the visa service provider in Armenia has since changed). It seems both Tech Nation and the Home Office were satisfied. Approval came a week later. As my wife put it: “I hadn’t even started waiting yet, and they had already replied.”

After getting the visa, I stayed in Yerevan for another six months. I can’t say I was eager to move anywhere, but by the end I was ready to start.

And yes — arrange shipping door to door, not to Heathrow Cargo. Everything there is geared toward B2B, and retrieving our 350 kilograms from there was nerve-racking. The rest, once again, went smoothly.

This move happened at the darkest time — around the longest night of the year. Personally, I take a long time to detach from the old. I returned many times to both Moscow and Yerevan. And with anyone who claims that London is unequivocally better than Yerevan (or Moscow, for that matter), I’d be happy to argue.

But in this chapter, let’s focus on London’s advantages. The density of opportunities here is completely different — in almost everything. Including for a child. You just need to know how to use them. I’m not entirely sure I’ve learned how to do that yet, even after a year.

The predatory snarl of capitalism — the hustle, aggression, stepping over others — appears, at first glance, to be less pronounced here than in Moscow (though, of course, more than in Yerevan). I’m well aware of the local statistics on stabbings and phone theft, but even so, the level of trust between people here is still noticeably higher.

By the way, I stopped clutching my phone nervously fairly quickly — and so far, it’s still with me. That said, everyone’s experience here is different.

London is a fairly unique immigrant city — and I’m not talking only about the past few decades. People here write texts very clearly and competently, but almost everyone (except schools and your accountant) ignores your emails. They treat adults like adults — yet if you happen to run into a “Danish dialect of British English” (something from the north of England that barely registers as English at all), they’ll calmly shout it back to you syllable by syllable through the post office window. After all, there are plenty of clueless immigrants like us wandering around here.

A brief note on local dialects: American pop culture does not prepare you for this. Not even close. If you want reference points, try the series Broadchurch or Department Q. If you understand everything there, you’re more than ready.

We had been to London several times before — both as tourists and for work. About ten years ago, we stayed in a hotel in Bayswater, a tourist area. Now we’re renting an apartment in the same neighbourhood. There’s a common practice here of subletting your flat while you’re away. As a result, my family had already lived in this apartment before, and we knew and liked the area. So when the previous tenants moved to Yerevan, it was an easy decision: we had to take it.

This is a good moment to reflect on the classic dichotomy between “a safe, white suburb with a good school in the middle of nowhere, dull as watching paint dry” and “a colourful city centre where everything is close, but someone gets stabbed under your windows at night.” Since people don’t always read sarcasm properly, let me say this clearly: I’m exaggerating in both cases.

Russians, as a rule, choose a school first (not all nationalities suffer from this Russian-Chinese condition). The main criterion is proximity to home: if you live nearby, your chances of getting in increase significantly. As a result, people pick some selective grammar school and then stubbornly search for housing nearby. That’s not our approach.

As you may have guessed, we consciously chose the second option — the colourful city centre. In everyday terms, this is “classic London”: an endless white five-storey Victorian building from the mid-19th century. While serfdom was being abolished in Russia, they were installing our windows and building the Underground here. One local quirk is a fake house façade behind which trains actually run — this spot even made it into Sherlock with Cumberbatch.

In winter, the cat gets blown away together with the rug. Gas and electricity cost around £150 per month in winter (significantly less in summer). Evening walks happen around Kensington Palace. Oh, and apparently there’s a new Banksy in our neighbourhood — we should go look for it.

That said, there’s also a third housing option: modern build-to-rent developments. It’s the classic setup — a station thirty minutes from the centre, a megamall, a high-rise with a co-working space and a gym. The cat definitely won’t get blown away there, but you can forget about the London vibe.

The first one is a public, non-selective primary school visible straight from our window, housed in a mid-20th-century brutalist masterpiece. I’m serious about the masterpiece part.

Only about 20% of the children there are native English speakers; the rest are extremely diverse — from Malaysia to Russia.

There’s a lot of open data like this in the city: you can easily check online the ethnicity, religion, income level, and age profile of most of your future neighbours. Nothing is hidden, and none of this is considered racist. If you’re from Russia, you’ll simply end up in the other whites category in the statistics.

London runs entirely on protocols: everything is documented, every move is recorded — and your expectations of continental European etiquette can safely take a break. This is the Island.

The second school is a secondary International Baccalaureate (IB) school, about a fifteen-minute walk away. It’s very much in the same spirit as the primary one — they’re proud of the fact that around 70 languages are spoken there. And they’re not exaggerating. The school is partly funded by a foundation established by an Iraqi Jew who once fled the Ba’ath regime and Saddam Hussein. The founder’s name is on the walls, along with a list of those languages.

Architecturally, the building matters too — it’s from a completely different era, but you could easily move a tech corporation into it and it would feel right at home.

At this point, it’s worth reflecting on the fact that neither of these schools fits the genre of “an elite St Petersburg school where the child develops a nervous tic and ends up hating everyone.” They’re just good, ordinary neighbourhood London schools with solid official ratings (which probably don’t mean much — but apart from those and anecdotal data points from friends, you don’t really have anything else to compare with).

In my view, studying in a relatively new language is already challenging enough for a child, without piling on selective schools and tutors from day one. Over the course of a year, she settled into the language quite well — now we can think about next steps.

These days I spend a lot of time at WeWork — it’s my default office. The constantly changing neighbours create a completely different world compared to working in the same office year after year. It shifts your perspective significantly.

I arrived with a background in corporate research, where you spend many years inside large organisations, doing complex investigations and protecting infrastructure. And suddenly you realise there are dozens of other possible trajectories. I had never looked at the world that way before.

My social circle is still mostly Russian-speaking, with one exception: the gym, which is fully international. One recent anecdote — a Brazilian woman asked me, “So, are you from Russia-Russia?”

“Yes,” I replied, “and even worse — from Moscow-Moscow.”

I think we understood each other perfectly.

I’ve also noticed that I’ve started answering “I’m Russian” with more pleasure since it stopped being particularly fashionable. Then again, being a Muscovite was never fashionable in Russia either — and somehow we all survived.

I communicate far more than I ever did before. This is probably because you have to find your footing in a new environment somehow. There are many people around me whom I would never have met in my previous life. It increasingly feels like a visa is not just the right to work, but also the beginning of a new stage. The number of opportunities has grown — now I need to learn how to see them.

If I could go back three years and talk to my Moscow self, I would tell him one simple thing: when you do have a choice (few of us really do, but still), the question “where to go” is actually secondary. The main question is “why.”

Every country has its own meaning, its own set of opportunities and constraints. If your goal is to maximise the income-to-expenses ratio, that’s one country. If your main priority is giving your child education and future opportunities, the choice will obviously look different. Or maybe what matters most to you is a gentler everyday life, more humane interactions, a sense of safety.

And in any case, you always take yourself with you. Nothing magical happens just because you change locations. A complainer will remain a complainer; a troublemaker will remain a troublemaker.

Relogate asked me about my dreams and the future. My first dream is work that is so engaging that, in the evening, there’s no question of “work or watch a movie.” Perhaps that will involve a shift within my profession — we’ll see. London seems to be exactly the place where such trajectories exist; I’m just still learning how to recognise them.

The second dream is purely domestic: to get a cat. The landlord has given permission — now I just need to find the confidence and overcome the thought that “this will complicate any future move or rental.” If you ever see a photo of me with a cat, you’ll know I’ve settled in.

And there is a bigger dream — one that was born not here, but much earlier: that the world would stop closing itself off. For twenty or thirty years, we lived in a reality where “yesterday it didn’t exist — today it does; yesterday it was forbidden — today it’s allowed; go ahead and do it.”

Now, as a global trend, we seem to be moving in the opposite direction.

Yes, this is about personal freedom — for ourselves and for our children (and, predictably, we’ve arrived at the conclusion that it’s not really just about education). And it’s not only about Russia. All of this searching for a place to live ultimately grows from there.

If we’re still around, we’ll see how it all turns out.